-->

To write this D’var torah, I am going to openly say that I

borrowed liberally from an excellent source; Elan, who does a weekly Torah

discussion either on You Tube or in print on the Mizrachi Canada Web Site (www.mizrachi.ca). The context is a bit

different, but the concepts are related.

Tisha B’Av is the saddest day in the Jewish calendar, with

multiple tragedies happening on this day dating back to the early years of the newly

liberated Jewish people wandering in the desert. The most auspicious events

that are commemorated, however, are those surrounding the destruction of the

Temple and the almost 2000 year-long exile from the land of Israel that

continued until the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948. The Temple

was the center of Jewish Religion and Culture in ancient times. All rituals

were tied to it, including daily sacrifices, and personal offerings for

thanksgiving and for transgressions. All

holidays were National celebrations with families ideally going to Jerusalem to

bring sacrifices at the Holy Temple and join in in a massive communal celebration

with all of Israel. The absolute centrality of the Temple to Jewish spiritual

life meant that the destruction of Jerusalem and its crown jewel, the Holy

Temple, left the Jewish People almost rudderless as they went into exile.

This tremendous tragedy has been the subject of significant

debate and discussion by Jewish commentators throughout history. Like the debate

over how the Holocaust could have happened, there is many theories posited as to

why G-d would allow the Temple to be destroyed. In Talmudic and Midrashic

literature, our Sages put forward many explanations. There is a clear theme to

them, and it revolves around how the people of Israel treated each other at the

time. The most prevalent explanation is “sinat chinam”, literally

baseless hatred; the inability of people to treat each other with respect or

with kindness. Other similar explanations specify actions where people took

unfair advantage of others, embarrassed people in public, or, as explained by

the famous early 2oth century Rabbi Naftali Tzvi Berlin (the Netziv) there was “excessive

righteousness”; people believed if one did not think, act or feel as they did,

that the other was a heretic and should be disrespected. Yet this was a nation

who was involved in rituals and for whom the Temple was central. What could

have led to such behavior?

In a recent Torah portion, Parasha Beha’alotcha, we get some

tremendous insight into human attitudes. The Children of Israel had recently left

Egypt, seen the Reed Sea split, received the Torah, and yet, they complained to

G-d about food, water, meat, as if they had no connection to the wonders they had

experienced. What could have led to this seemingly irrational behavior?

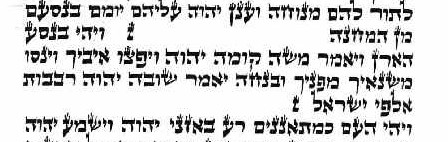

The Kli Yakar, a commentator on the Torah, points out that

in this parasha, there is a strange annotation to the text (see below); the

letter Nun “]” is written twice, backwards, as if to bracket the words “min

Hamachaneh” (from the encampment) away from the famous verse Va-Yahi Binsoa Ha-aron” “When the Ark was to set out, Moses would say: Advance, O LORD! May Your

enemies be scattered, And may Your foes flee before You!”

Why the bracket? Why an annotation here that is not found

elsewhere in Torah? The Kli Yakar explains that the backward “]” facing away

from the word “Ark” and toward the word “encampment” means that rather than

looking towards G-d for guidance, that people were looking towards the others,

trying to be pious or righteous in the eyes of the others, not really

connecting with G-d but remaining very insular. Being insular is a hindrance to

growth, and really means that you do not have your ‘eye on the prize’ but

rather your vision is misdirected.

If this has a familiar ring to it, it’s because we are

living in very disturbing and thoroughly crazy times. There is a complete

blurring of the lines between truth and lies, between what the worlds sees and

what the world believes. This week we were treated to various Trumpian takes on

Russian intervention in US politics, but things go way beyond that. The left

and the right have no ability to engage in civil discussions; many believe one’s

own position is correct therefore you do not have to listen to others. This is

the “excessive righteousness” that the Netziv intimated was the downfall of the

people of Israel. Moreover, terrorists are freedom fighters and defenders

against terror are disproportionate aggressors. And where are people getting

their inspiration from? A small screen in their hands; from selfies and blogs

of like-minded people.

Yet, we have role models of people who did not look inwards

all the time, who looked at others as important individuals, were always able

to listen and lend a helping hand. Michael Samuel, Papa to many, was the

ultimate role model for Tzedaka and Chesed, acts of charity and lovingkindness.

He always had time for others, whether it was for his family, synagogue,

community organizations, or clients. He always would give advice, or just be

there if you needed him. The most important lesson is that he treated everyone

with the utmost respect, no matter how old or young, how rich or poor. This

ability to respect everyone is what is missing from the leftwing-rightwing

debates of today. The ability to respect is the ability to see that all are

created equal, a concept embodied in the teaching that all people are made “B’tzelem

Elokim”; in the image of G-d. To respect others, don’t just look towards the

encampment; that is too insular. Look towards the Aron, the Ark of G-d, see the

light shining in all. If the world would only learn the principle of respecting

others, so beautifully embodied by Mike, we could potentially have a world

where the lessons that led to the destruction of the temple are learned and

people could live together in harmony.

May we learn this crucial lesson and help bring peace and

respect to the world. May Michael ben Mordechai always be a shining example for

us and his memory forever a blessing.

Shabbat Shalom

(To those observing Tisha B’av, have a meaningful fast)